Publications

Journal der Künste 23

Published three times a year (German/English), available free of charge

ISSN (Print EN) 2627-2490

not yet published

The first issue of Journal der Künste under the presidency of Manos Tsangaris and Anh-Linh Ngo focuses on artistic freedom. Texts by Lena Gorelik, Ralf Michaels, Carsten Wurm and others as well as a conversation with Kristóf Kelemen and Gergely Nagy from Hungary address the defence of artistic autonomy from various perspectives. Further contributions provide insights into the genesis of the current exhibitions and the work of the archive.

Journal der Künste 22

Published three times a year (German/English), available free of charge

ISSN (Print EN) 2627-2490

The Journal der Künste, issue 22, bids farewell to Jeanine Meerapfel and Kathrin Röggla, the Akademie’s former president and vice-president. It explores the possibility of utopias with Matěj Spurný, Eva von Redecker and Iris ter Schiphorst and the political shift to the right in Germany with Thomas Krüger, Christina Clemm and Holger Bergmann. The 2023 Kollwitz Prize recipient, Sandra Vásquez de la Horra, shows works from her oeuvre; and a Carte blanche designed by Wolfgang Tillmans is featured. The archive includes the stories behind a photomontage by István Szabó and newly acquired drawings by George Grosz, as well as insights into Jürgen Flimm’s director’s workshop.

Archive zur Musik des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts, Band 16 Gerd Kühr

Werner Grünzweig im Auftrag der Akademie der Künste, Berlin

von Bockel Verlag, Neumünster 2024

German, 176 pp.,

25 ill.

ISBN 978-3-95675-047-2

Best.-Nr. 3055

€ 29,80

Composer Gerd Kühr (b. 1952 in Carinthia, Austria) studied under Hans Werner Henze, among others. He experienced his breakthrough in 1988 with the opera Stallerhof, based on the play by Franz Xaver Kroetz. To this day, he has devoted himself primarily to music theatre. In addition to an extensive interview with Gerd Kühr and an inventory of the Gerd Kühr Archive at the Akademie der Künste, the publication contains important texts by the composer.

Kolja Lessing

Ursula Mamlok

Composer between New York and Berlin

Hermann Simon

Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin Leipzig 2024

German, 82 pp.,

19 ill.

ISBN 978-3-95565-636-2

Best.-Nr. 3054

€ 8,90

Even in her youth, Ursula Mamlok (1923–2016) had one single career goal: to become a composer – despite all the adversity of 1930s Berlin, which she left with her parents at the last minute in 1939. In New York, the struggle for her compositional identity began. After a successful career in the USA, the grande dame of contemporary music ventured a new beginning in Berlin in 2006 after her husband Dwight Mamlok passed away.

Journal der Künste 21

Published three times a year (German/English), out of print

ISSN (Print EN) 2627-2490

The 21st issue with a new design focuses on questions of sustainability: with texts and photo series on “The Great Repair” by Anh-Linh Ngo, Zara Pfeifer and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, among others, and literary contributions by Ulrike Draesner and Cécile Wajsbrot. Also: conversations with Luc Tuymans and Gundula Schulze Eldowy, short essays by Anna Hetzer, Moshtari Hilal et. al. as well as news from the Archives.

Peter Ablinger, Now! Writings 1982–2021

Übers. ins Englische von Meaghan Burke, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Verlag MusikTexte, Köln 2022

English, 320 pp.,

ca. 80 ill.

ISBN 987-3-9813319-8-1

Best.-Nr. 3053

€ 29

“The sounds are not the sounds! They are there to distract the intellect and soothe the senses.” Born in Austria in 1959, Peter Ablinger, who has lived in Berlin since 1982 and is a member of the Akademie der Künste, is not only considered to be an innovative composer but also a brilliant essayist. His writings were published in German in 2016 and are now available in English translation.

Jean Barraqué

Sonate pour piano

Bd. 1: Partitur

Bd. 2: Kommentar

Heribert Henrich (ed.)

Akademie der Künste, Berlin / Bärenreiter, Kassel 2019

German/English,

2 vol.: 53 and 132 pp., 2 facsimiles

ISMN 979-0-006-56760-7

€ 59

Sonate pour piano (1950–1952) by Jean Barraqué (1928–1973) enjoys a legendary reputation as probably the earliest attempt to reconcile the idiom of integral serialism with a monumental form. The work is now presented in a new critical edition, for which all handwritten and printed sources were subjected to an in-depth analysis and evaluation for the very first time.

Archive zur Musik des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts

Band 15

Eduard Erdmann

Werner Grünzweig and Gerhard Gensch on behalf of the Archives of the Akademie der Künste (eds.)

Akademie der Künste, Berlin / von Bockel Verlag, Neumünster, 2018

German

212 pp., 47 b/w ill.

ISBN 978-3-95675-024-3

Best.-Nr. 3041

€ 24,90

At the start of the 1920s, Eduard Erdmann (1896–1958) made a name for himself as a pianist and composer. The present volume is dedicated to his compositional oeuvre, his personality and his contacts to artists in Berlin in the 1920s, such as Ernst Krenek and Hans Jürgen von der Wense. An edition on his correspondence with Artur Schnabel and essays about Erdmann's ties to Riga complete this overview of the artist.

Werner Grünzweig

Artur Schnabel. Musician and Pianist

Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2017 (Jewish Miniatures, vol. 205a)

English

76 pp., 14 ill.

ISBN 978-3-95565-288-3

€ 8,90

Werner Grünzweig, who has published numerous books about Artur Schnabel (1882–1951), presents the first biography of Schnabel in German with this volume. It honours Schnabel as a performer, composer and theorist. His concert activity, records, publications and lectures have changed our concert life up to the present day.

Von Berlin nach Los Angeles. Die Musikwissenschaftlerin Anneliese Landau

Daniela Reinhold on behalf of the Akademie der Künste, Berlin (ed.)

Akademie der Künste / Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin, 2017

German, 340 pp., 15 ill.

ISBN 978-3-95565-226-5

Best.-Nr. 3044

€ 27,90

As a young musicologist, Anneliese Landau (1903–1991) was at the beginning of a promising career. In 1933, she was left with only the activities for the Jewish cultural association. In 1940, she emigrated to the United States and soon found a new home in Los Angeles, where she worked as the Music Director of the Jewish Center Association. Her autobiography, together with extracts from letters from her parents who remained in Berlin as well as Landau’s correspondence with composers, have now been published for the first time.

Archive zur Musik des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts, Band 13

Alexander Goehr

Fings ain't wot they used t'be

Werner Grünzweig (Ed.)

Akademie der Künste, Berlin / Wolke Verlag, Hofheim 2012

English, 160 pp.

facsimile, with Audio CD

ISBN 978-3-936000-28-3

Best.-Nr. 3043

€ 24

With contributions by Paul Griffiths and Werner Grünzweig and a autobiographical essay by Alexander Goehr

Catalogue of the music manuscripts in the Alexander Goehr Archive

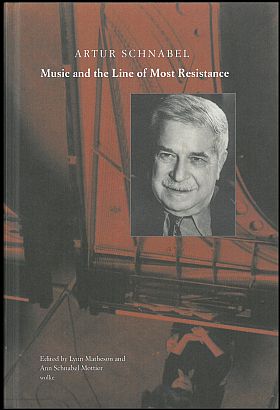

Artur Schnabel

Music and the Line of Most Resistance

Lynn Matheson and Ann Schnabel Mottier (eds.)

Akademie der Künste, Berlin / Wolke Verlag, Hofheim 2007

144 pp.

ISBN 978-3-93-6000-51-1

Best.-Nr. 3037

€ 24

With musical masterpieces, you never come to an end because every interpretation is merely an approximation of an unattainable ideal. To this day, Schnabel’s main argument in the lectures held in Chicago in 1940 represents a valid polemic position for every serious musician.